Mark Carwardine is a zoologist, TV and radio presenter, wildlife photographer and bestselling author. He’s written over 50 books about wildlife, travel and conservation including bestsellers like Last Chance to See and Mark Carwardine’s Guide to Whale Watching in Britain and Europe. In his latest book, an outstanding field guide, Mark Carwardine details the identifying traits and distribution of all 90 species and subspecies of Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises.

Mark Carwardine has taken the time to sign a limited number of first edition copies of the Handbook of Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises and answer our questions about the book, his life studying whales and humanity’s role in their survival.

- In your recent books, you’ve given us an insight into the world of whale watching. What motivated you to study cetaceans?

I’d just finished studying zoology at university (I couldn’t have done anything else – all I’d ever wanted to do since I can remember was to work with animals) and I had my first whale encounter. I was 21 years old, on a half-day trip from Long Beach, California, when a grey whale suddenly breached right in front of me. In my mind’s eye, I can see it leaping out of the water and remember deciding – at that very moment – that I wanted to spend as much of my life with whales as possible. Now I am a self-confessed whale addict and need to see a whale at regular intervals just to survive normal daily life.

Also, I think it is an incredibly exciting time to be a cetologist. These enigmatic marine mammals are incredibly difficult to study – they often live in remote areas far out to sea and spend most of their lives out of sight underwater – yet we now have access to space-age technology that, at last, is revealing some of their best-kept secrets

- You must have many stories about whales, dolphins and porpoises. What is your most memorable encounter with cetaceans?

I think it would have to be with the friendly grey whales in San Ignacio Lagoon, Baja California, on the west coast of Mexico. These 14-15-metre whales literally nudge the sides of our small whale-watching boats and lie there waiting to be tickled, scratched and splashed. Incidentally, if you’re wondering if it’s a good policy to encourage people to touch wild whales, consider this: if you don’t scratch and tickle them, the whales simply go and find a boat-load of people who will. Even the local scientists approve.

Yet it’s hard to believe that these very same grey whales once had a reputation for being ferocious and dangerous; when they were being hunted they fought back – chasing the whaling boats, lifting them out of the water like big rubber ducks, ramming them with their heads and dashing them to pieces with their tails. Nowadays, they positively welcome tourists into their breeding lagoon. Somehow, they seem to understand that we come in peace and, far from smashing our small boats to smithereens, they are very gentle and welcome us with open flippers. They seem to have forgiven us for all those years of greed, recklessness and cruelty – and trust us, when we don’t really deserve to be trusted. It’s a humbling experience, to say the least. I’m very lucky – I have been to San Ignacio more than 70 times over the years – but it still blows me away. It’s got to be one of the greatest wildlife encounters on Earth.

- Whales and other cetaceans are beloved worldwide, what is it about these charismatic creatures that humans connect with so strongly?

No one ever says, ‘I can’t remember if I’ve seen a whale’. A close encounter with one of the most enigmatic, gargantuan and downright remarkable creatures on the planet is a life-changing experience for most people. At the risk of sounding irrational and unscientific, a close encounter with a whale simply makes you feel good. Actually, it’s more than that. Just a brief flirtation with a whale is often all it takes to turn normal, quiet, unflappable people into delirious, jabbering extroverts. On the best whale watching trips, almost everyone becomes the life and soul of the party. Grown men and women dance around the deck, break into song, burst into tears, slap one another on the back and do all the things that normal, quiet, unflappable people are not supposed to do. I have seen it so many times.

It’s not really surprising: whales and dolphins are shrouded in mystery, yet the little we do know about them is both astonishing and awe-inspiring. They include the largest animal on Earth (the blue whale – the length of a Boeing 737) and some of the oldest animals on Earth (one bowhead whale was 211 years old when it was killed by aboriginal whalers – who knows how much longer it might have lived?) as well as the deepest diving mammal, the mammal with the longest known migration, the loudest singer, the largest carnivorous animal, and many other astonishing record-breakers.

- What advice would you give to the naturalist interested in cetaceans and wanting to learn more?

Read my new Handbook of Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises (I couldn’t say anything else, could I?)! It includes everything you could possibly want to know about all 90 species.

- What was the most challenging thing for you when creating this guide?

Well, it dominated my life for six years. I used to lie awake at night, worrying about whether to describe something as ‘blue-grey’ or ‘grey-blue’. I decided to go back to original sources for everything, which meant reading 11,000-12,000 scientific papers, poring over decades of my own field notes, and studying untold numbers of photographs and video clips. I also corresponded with species experts all over the world; they were all incredibly generous with their information and advice, often giving me new data before it has been published in the scientific press. I worked with three outstanding artists, too – Martin Camm (who did most of the illustrations), Toni Llobet and Rebecca Robinson – who, between them, produced more than 1,000 original and meticulous artworks. And as for the distribution maps… some of those took several days each. But, I have to say, it’s incredibly satisfying to see it all come together in this one book.

- What are your concerns or hopes for the future of cetaceans?

Sad to say, human impact has now reached every square kilometre of the Earth’s oceans. In particular, commercial whaling and other forms of hunting, entanglement in fishing nets and myriad other conflicts with fisheries, overfishing, pollution, habitat degradation and disturbance, underwater noise, ingestion of marine debris, ship strikes and climate change are some of the main threats being faced by whales, dolphins and porpoises around the world. We’ve already lost the Yangtze river dolphin, from China. The next to go is likely to be the vaquita, a tiny porpoise from the extreme northern end of the Gulf of California in western Mexico; there are probably just 10 survivors clinging on against all the odds. But the good news is that, with proper protection, we can make a difference. Whaling pushed the humpback whale to a population low of fewer than 10,000, but now there are at least 140,000 and counting.

- You say this will be your last book: now this guide is complete, are there any other projects in the pipeline?

Ah, yes, I did promise my family and friends that this would be my last book (by way of an excuse for never having any free time)! It feels like the culmination of a life’s work with whales and dolphins – and it will be my sixtieth book, which seems like a nice round number to finish on. But the trouble is that I love writing and have lots more ideas! In fact, I am working on a photographic book about the polar regions with the landscape photographer Joe Cornish (he is providing the landscape pictures, me the wildlife ones) – so I’ve already broken the promise. Apart from that, I’ve been setting up some new whale watching trips and am planning to do more radio programmes (I’ve missed doing radio), among many other things; and, of course, there is an awful lot to do on the conservation front that will keep me busy for a long time yet.

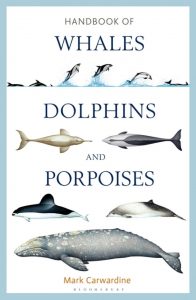

Handbook of Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises

Hardback, Nov 2019, £29.99 £34.99

This outstanding new handbook to Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises is a comprehensive and authoritative guide to these fascinating mammals.

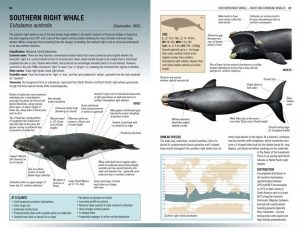

With almost 1,000 detailed, annotated illustrations, this new handbook describes all 90 species and subspecies.

Signed copies available, while stocks last.

Browse our full range of cetacean books.