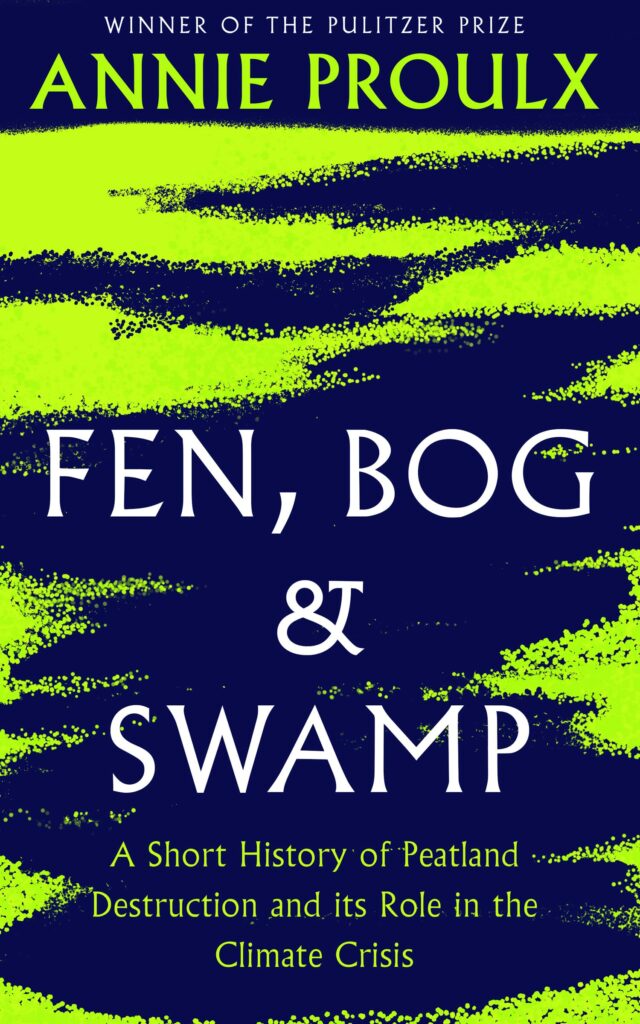

Fen, Bog & Swamp, from Pulitzer Prize winning author Annie Proulx, is a wide ranging book that meanders through the subject of wetlands on a journey which encompasses history, biology, language, culture, art and literature. Written in a passionate and lyrical voice, the book is not only a thorough exploration of these ecosystems, but also a war cry in their defence, although one that at times feels dampened by the assumption of inevitable defeat. This is echoed in a statement in which she describes her intentions behind the writings and research: “Before the last wetlands disappear I wanted to know more about this world we are losing. What was a world of fens, bogs and swamps and what meaning did these peatlands have…”.

Fen, Bog & Swamp, from Pulitzer Prize winning author Annie Proulx, is a wide ranging book that meanders through the subject of wetlands on a journey which encompasses history, biology, language, culture, art and literature. Written in a passionate and lyrical voice, the book is not only a thorough exploration of these ecosystems, but also a war cry in their defence, although one that at times feels dampened by the assumption of inevitable defeat. This is echoed in a statement in which she describes her intentions behind the writings and research: “Before the last wetlands disappear I wanted to know more about this world we are losing. What was a world of fens, bogs and swamps and what meaning did these peatlands have…”.

The book is arranged into four loose parts: an introduction of “discursive thoughts on wetlands”, followed by individual chapters covering fens, bogs and swamps. Beginning the text with a description of a fond yet distant memory of walking through a swamp with her mother as a child in 1930s Connecticut, which she describes as her “first thrill of entering terra incognita”, Proulx goes on to bemoan the disinterest of modern humans in “seeing slow and subtle change” and the “slow metamorphoses of the natural world”. In our fast-paced lives in which speed and efficiency are hailed as the twin gods of progress, there are few who can, or desire to, repetitively observe the same flowers, trees or waters, week after week, season after season, or to appreciate the myriad yet microscopic ways in which they change. For this reason, evidence for a warming climate and its impending crisis have been easy to ignore until the impacts are so visible that they can no longer be shuffled under the carpet.

As a reader based in Britain, I found the section on fens to be of particular interest, despite the fact that their story is ultimately one of destruction and decline. These days it is hard to imagine a Britain in which 6% of the land was wetland, all of which provided a “source of wealth that could hardly be surpassed by any other natural environment”. Now, in modern Britain, less than 1% of the original fenlands remain: a mere fragment of this once great and diverse habitat.

Proulx’ wonderful descriptions of the people who lived in the fens and how an intimate knowledge of its creeks, rivers and mudflats allowed them to thrive in this challenging landscape are particularly pleasing. Using descriptions of artwork and quotations from literature (such as the Moorlandschaften photographs of Wolfgang Bartels and Gertrude Jekyll’s wonderful vignette on the use of rush-lights) Proulx paints a vivid picture, not only of the historical landscape, but also of the lives of the people inhabiting them.

In fact, these diversions into the lives of the people who have impacted and been impacted by wetlands occur frequently throughout the text, and are used to great effect to provide an insight into changing minds and cultures. From stories of the 16th century Spanish explorers to those of naturalist Henry Thoreau and botanist William Bartram, the book is littered with potted biographies that tell the stories of the people who were fascinated by these landscapes, as well as the darker sides of exploitation and greed.

Through the telling of these stories, it becomes apparent that fens, bogs and swamps have long been derided by humans. This is exemplified by the pre-15th century British fen dwellers who were “literally and metaphorically looked down on” by the upland people in a manner that was reflected in their view of the fenlands themselves. Also mirrored in the attitude of European settlers in the US who despised the swamps for slowing down movement and progress and limiting productive agriculture, wetlands throughout the world have consistently been viewed as ‘waste, unproductive’ areas, in need of ‘improvement’.

Time and time again we have blundered around in the name of progress, attempting to drain, farm, reforest and develop these regions with little knowledge of how to maintain them afterwards, or even whether this is possible. Indeed, as is now apparent in areas such as New Orleans and Chicago, where the water is slowly taking back the land, the fight against nature is likely to be a long drawn-out game that we are unable to win.

As you might expect from someone whose life has been concerned with words, Proulx pays a lot of attention to the language surrounding fens, bogs and swamps. Highlighting such examples as the equally pleasing Pocosin (swamp) or Muskeg (bog), she also draws parallels between the loss of these habitats and the loss of the language that we can usefully use to describe them. In a manner that has also been highlighted by writers such as Robert MacFarlane in Landmarks and The Lost Words, it seems that this is a two way street: as we lose the habitats, we also chip away at the list of nouns and adjectives that are used to describe them; but equally, with the loss of this nuanced language, we also begin a process of forgetting and dismissing the landscapes themselves.

I came away from reading this book with a new appreciation of fens, bogs and swamps, but also saddened by the fact that, as Oliver Rackham stated, the long history of wetlands is ultimately a story of their destruction. As Proulx simply states in her final lines, in an echo of those words from Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It, perhaps the time is coming when we will all be “haunted by waters”.

Fen, Bog & Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and Its Role in the Climate Crisis is available for pre-order from NHBS and is due for publication in September 2022.