Otherlands is the exquisite portrayal of the last 500 million years of life on Earth. Palaeobiologist Thomas Halliday takes readers on an exhilarating journey into deep time, interweaving science and creative writing to bring to life the unimaginably distant worlds of Earth’s past. Each chapter is an immersive voyage into a series of ancient landscapes, throwing up mysterious creatures and the unusual landscapes they inhabit.

Otherlands is the exquisite portrayal of the last 500 million years of life on Earth. Palaeobiologist Thomas Halliday takes readers on an exhilarating journey into deep time, interweaving science and creative writing to bring to life the unimaginably distant worlds of Earth’s past. Each chapter is an immersive voyage into a series of ancient landscapes, throwing up mysterious creatures and the unusual landscapes they inhabit.

Thomas Halliday has kindly taken the time to answer a few questions for us below.

Could you begin by explaining what you mean by ‘otherlands’? How did your fascination with these ‘otherlands’ begin and what drew you to write about this?

The word ‘otherlands’ came about in trying to come up with a title that reflected some level of familiarity and strangeness. It falls somewhere between the idea of something being ‘otherworldly’, but also recalls ‘motherland’ – a safe, familiar home. I think all palaeobiologists, whatever subdiscipline they are part of, have the shared goal of understanding how life used to be. Biomechanists might concentrate on the engineering of a skeleton to understand the behaviours it would have been capable of, and phylogeneticists are interested in how living things are related and changed over time, but all of it adds up into a picture of past life. I’ve always been more interested in big picture, ecological questions rather than the minutiae of anatomy – as important as anatomical knowledge is – and so writing through an ecological lens made most sense to me. In essence, it’s just putting down on paper what we as a community have discovered about life at different points, which is a useful exercise in bringing together science from groups who don’t necessarily read one anothers’ papers. I can’t visit these places except through some creative process – whether that’s a painting, an animation, or text. And I can’t paint or animate.

It is a great feat of work to bring Earth’s deep past to life and to render the unseeable things seeable through prose. How did you approach such an immense task from not only a literary perspective, but a philosophical and scientific perspective too?

Every site in the book has some kind of layout in my mind. It may be known to a fairly high degree of accuracy scientifically – the extent of the playa lake in Moradi, just over 250 million years ago in what is now Niger – is sketched out in papers on that site, so we can get an estimate of how big it was, and which way the water was flowing from. In others, our knowledge is a bit more generic but I have a mental map of where the different beats take place. The line of the story in each place moves through that space, which means that I can be consistent in timing, sights and so on. I think this internal consistency of a place is essential to making it seem immersive. Most of the actual visual descriptions of the animals and plants I use, though in my own words, are no more detailed or evocative than those of other writers, so if I have managed to create a better sense of things being ‘seeable’, as you suggest, then I think that it is everything else around it that make the scene believable. If the scene has been describing the smell of a limestone cave, that colours the subsequent description of the next animal, because mentally you begin to frame it as seen while emerging into the light. We experience an environment through all our senses, and so appealing to those other aspects of reality brings out the realness of an organism.

One of the things I most appreciated about Otherlands was how you focus on landscapes, the settings that are necessary for life to evolve, versus our society’s sensationalised image of the prehistoric world that typically conjures up images of monstrous creatures. What is it that draws us to the dinosaurs compared to the often forgotten plants, fungi, invertebrates and other species?

I blame Gideon Mantell. Well, not really, but the early pioneers of popular geology at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century drew crowds because of the enormous creatures they could put on display. The first fossil animals to be displayed in sensationalist shows were mastodons – relatives of elephants – and giant ground sloths. You have to remember that this is a pre-Darwinian time, when extinction has only recently been recognised, and when the timescale of the age of the Earth is still very much debated. They drew in the crowds with claims of antediluvian monsters from some barbaric era, and I think a lot of the popular depictions of the past have remained since then. If you think of the most influential European and American artistic works featuring palaeontology over the last – Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth, Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, Disney’s Fantasia, all the way through the Ray Harryhausen B-movies to Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park, there’s a common thread of violence and peril, which is undoubtedly a crowd-pleasing approach but doesn’t really reflect what biology is typically like.

That doesn’t quite explain why many fossil mammals or crocodilians, for instance, are poorly known by the public. Dinosaurs do have the advantage of being typically very large compared with the biggest land animals of today – and indeed the recent past – so if you’re going into a museum it’s a lot harder to miss the big Diplodocus than the display of fossil horsetails. There is something awe-inspiring in size, but I hope that people can take the time here to recognise the wonder in the very small things that are going around. I do of course have dinosaurs in the book, but because they have been covered so extensively, I didn’t want to deal with many of the clichés. There’s a dinosaur hunting for food, sure, but it ends in failure. The big tyrannosaur has a drink and scratches off some dandruff against a tree. There’s more to dinosaurs than violence.

I was struck by the level of detail that is revealed from the fossil record, to the point that we can know the presence of different types of insects based on the distinct ways in which they damage leaves. As you collated such an array of research for the book, were there any particular findings that captivated your imagination the most?

One piece of information that I really enjoyed learning about, just because of the implications throughout, was one that I picked up at a conference talk (and which has since been peer reviewed and published). Oviraptorosaurs are a group of dinosaurs that have been associated with nests for a long time. The name means ‘egg thief reptiles’ because it was initially assumed that they were eating the eggs, but more and more finds have accrued, including of parents sitting on the nests at the time of burial, that show that these are their own nests that they are caring for. We can reconstruct how the nests were built based on the arrangement of eggs and the nest mound – a ring of eggs was laid, and then buried, and another ring later added. But what is wholly remarkable is that we can chemically analyse the eggshells even now, and identify different isotopic ratios of calcium in each layer. The isotopic pattern is a sort of chemical signature that is tied to the individual mother that provided the raw material for the eggshell. What this means is that each nest contains the eggs of more than one mother. There are a couple of possible explanations for this, but the best modern example of communal nesting like this is in ostriches, where a single male builds and guards each nest, and several females lay eggs in the same nest. In ostriches, the males then rear the chicks once hatched – I don’t go so far as to claim this for oviraptorosaurs, as this could only be speculation, but I think the best examples of fossil record detail are those where a preserved detail of chemistry opens up a whole trove of behavioural implication.

Scientist Robert H. Cowie writes: “Humans are the only species capable of manipulating the biosphere on a large scale. We are not just another species evolving in the face of external influences. In contrast, we are the only species that has conscious choice regarding our future and that of Earth’s biodiversity.” Speaking to this, how can our current epoch defined by destructive human influence be compared to these past worlds, and what lessons might be learned?

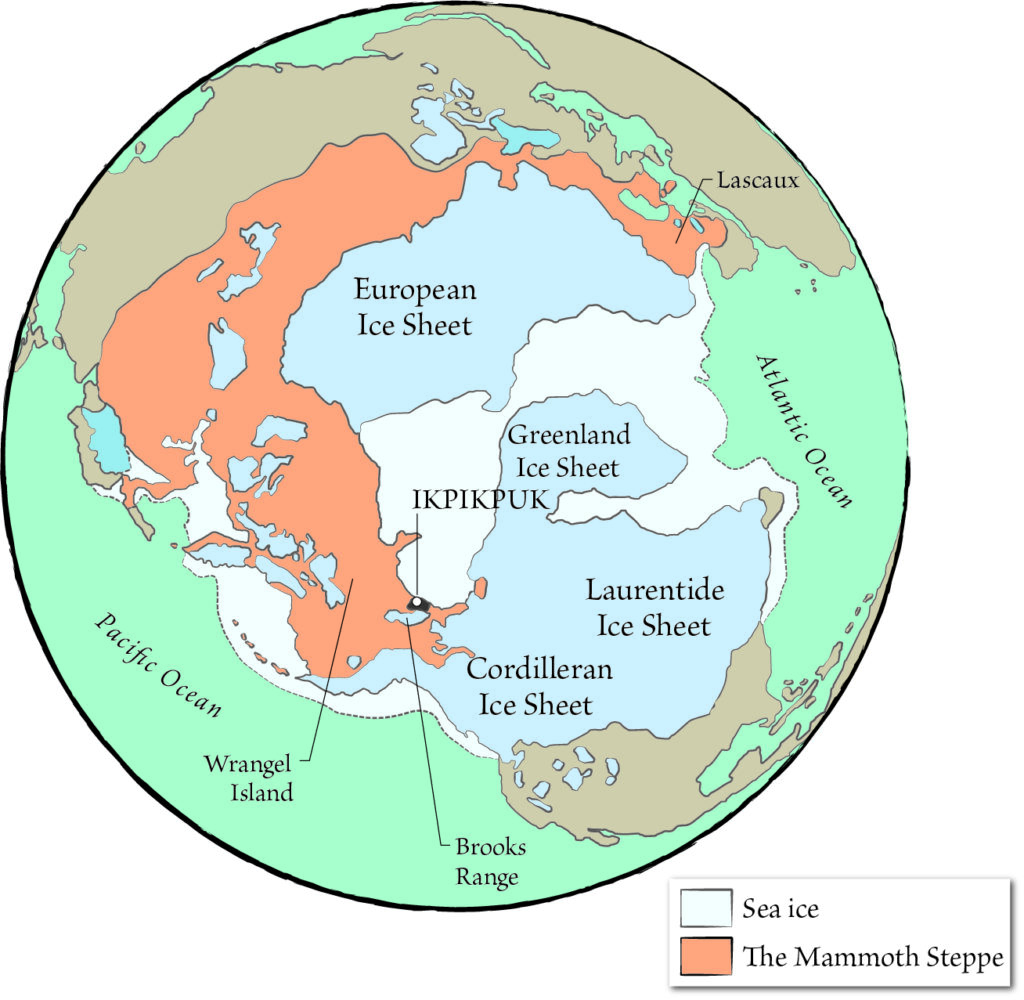

Our epoch is known as the Holocene, and makes up the last 11,700 years of geological time. Human environmental influence extends past the beginning of the Holocene, but recently it has been both accelerating and fundamentally changing in type. With deep ocean dredging and drilling, we are disturbing ecosystems that had until now never encountered us, plastic is pervading every part of the biosphere, we are altering the atmosphere globally, and our consumption of resources has boomed. When we look to the past, we find a few occasions when some similar traits can be observed. New chemicals in an environment – from oxygen in the single-celled earth of the Proterozoic to wood in the Carboniferous – have disturbed the balance of the world, but ultimately incorporated in fundamental processes. The Great Oxygenation Event is widely suggested to have caused a turnover in microbial communities as those oxygen-intolerant species retreated to environments this new toxic gas could not reach. The delay between the origin of wood and the development of lignin-digesting bacteria has been suggested as a reason for the preponderance of peat forming swamps in the Carboniferous, although this is disputed. Whatever the reason, the laying down of peat – and then coal – changed the atmosphere radically, which led to greater aridity worldwide, ultimately destroying the suitable environment for the very trees that had caused that change. But the biggest effect we are having is that of disturbance, and for that we have to look to mass extinction events for parallels. Earth has existed in all kinds of climatic states over its history, but mass extinctions have occurred during times of sudden transition. From the end-Ordovician, when glaciers rapidly advanced and retreated from the poles, to the end-Permian, when unfathomably large volcanic eruptions deoxygenated the oceans and threw greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, to the end-Cretaceous, when the aftermath of a meteorite impact darkened the skies for years, rapid change is typically bad. Although life eventually returns, it can take millions of years, and the species that thrive afterwards are rarely those that had thrived before.

Our effects are often extreme and rapid, and part of the problem is that they are done with a short-term mindset. Some human modifications – such as the pre-Columbian cultivation of the Amazon rainforest, the development of clam gardens, or well-managed meadowlands – have increased diversity locally, and are sustainable in the long term. We mustn’t fall into the trap of thinking that humans can only be destructive, or that we are separate from the ecosystems we live in. But, looking to the past, it is clear what the consequence of destructive behaviours is. This is the Earth we live in, and we are part of this world, but worlds can change in a moment.

This book is a timely reminder of the impermanence of life on Earth, evocatively revealing the fragility of our existence. As a researcher of the past, what do you see for our future?

People often assume that I might answer this question in terms of biology of life after humanity, or of the evolutionary direction humans are heading in. Although speculation can be fun, I don’t think that’s a useful way of thinking, because as Earth history shows us, the broad strokes of biology will remain the same. There will always be the same patterns of energy flow through ecosystems, and amazing adaptations to environments so complex that to form any predictions of the truly long term is futile. But we must think ahead to our immediate future. Nobody is suggesting that humankind will become extinct any time soon – we are too generalist, too adaptable to any environment to suffer that kind of loss. But that doesn’t mean that people, societies, cultures will not suffer under the environmental change that is already underway. And of course, portraying climate change as something that is future is itself untrue; we have been feeling the effects of climate change for decades already, especially those of us in low-lying island nations, those prone to storms, or dependent on seasonal ice. The effects will continue to accrue and to spread, but I remain optimistic that we will do what needs to be done – cease extraction of fossil fuels, move to a less all-consuming society, and support less wealthy countries in improving quality of life through renewable energy rather than repeat the errors we have repeatedly made. I am optimistic, and hopeful, but it is not something that will just happen. I see hard work, and that it will be entirely worth it.

Otherlands: A World in the Making

Otherlands: A World in the Making

Hardback | £19.99