With the publication of the October issue of British Wildlife, the magazine has reached 30 years in print. British Wildlife found its home here at NHBS in February 2016, but it owes its existence to founders Andrew and Anne Branson, who first brought it to press back in 1989. In our 30th anniversary issue, we were delighted to learn more from Andrew about the earliest days of the magazine.

A shortened version of Andrew’s piece, ‘British Wildlife – how it all began’, is included below. To find out how to read the full article, see here.

Taking ‘the path less travelled’ has often been a failing of mine. In early 1988, after another week of commuting up to London as a publisher for a large multinational publishing house, I came to the conclusion that there must be a more enjoyable way to earn a living. Perhaps not such an unusual thought, but what surprised colleagues were that I then effectively headed off into the ‘undergrowth’ of rural Hampshire to set up British Wildlife Publishing, with the support of my wife, Anne. My work had allowed me to spend days in the field with some great naturalists, and through discussions with those it became obvious to me that there was a need for something different that captured the expertise of some of our best field naturalists, provided up-to-date information on the rapidly changing world of conservation and, importantly, was also a first-class read.

In the 1980s it was still the case that, by and large, people were much more blinkered in their interests. For example, birdwatchers seldom took note of other groups of animals and plants and the entomologists were generally a small, tight-knit group of specialists. I was looking for something that would break out from this bunker mentality and act as a showcase for the great work being done in British natural history.

There were, of course, numerous scattered membership magazines and journals for the various specialist societies, each promoting its own agenda, but how could you find out what was happening with wildlife around the country? Sometimes the journals reported on events years after they had happened. And remember, this was before the days of emails and social media. Communication was all about telephone calls and letters; networking was down to attending conferences and field meetings. In the end, I worked from the premise that, if it excited me and I would buy it, then others, too, would do the same.

I was also increasingly aware of the work of the Nature Conservancy Council (NCC), not only in advising the government on contentious issues but also in producing detailed research documents. At an early stage in planning the magazine, therefore, I visited this important hub of expertise in Peterborough. A good working relationship with this team was critical and I received a warm welcome from Philip Oswald, the communications boss, who introduced me to several people who became key contributors.

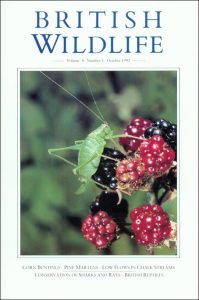

Bringing all this together in 1988, I decided to create a completely new magazine that would cover all aspects of wildlife and nature conservation in Great Britain and Ireland, and that, despite its broad geographical remit, it would be called ‘British Wildlife’. The watchwords of the publication were to be accuracy, independence of view and quality. The proposed contents were to include a mix of articles and news which deliberately juxtaposed information on subjects as diverse as bryophytes and birds, flies and flowers, conservation news and reserve management. Planning the potential contents was relatively straightforward, but coming up with a team of people that would put it together was another thing.

The first issues

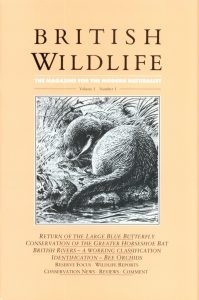

The first issue of British Wildlife came out, after a long hot summer (one computer caught fire!), in October 1989. We printed 5,000 copies and initially sold just under 2,000, but within a few years, they had almost all been sold. In addition to the various in-depth articles, the first issue included the wildlife reports, pretty much as they are today, with, extraordinarily, still some of the same contributors: here we find the butterfly news written by Nick Bowles, moths by Paul Waring and flies by Alan Stubbs. Peter Marren, then working for the NCC as a writer, and his inimitable column ‘Twitcher in the swamp’, appeared in the fourth issue and there he has remained, with the odd holiday, right up to today. After struggling at first to find a hero to take on the herculean task of sifting through newspaper cuttings and press releases to produce ‘Conservation news’, Sue Everett came to the rescue in 1991 and has ever since been ably riding the waves of news, including, more recently, the tsunami of information that now floods the internet.

Herein lies one of British Wildlife’s great strengths: a reliable team of highly knowledgeable and talented contributors that have been with the magazine, through thick and thin, for decades. I take my hat off to them all.

Some great names and articles

Happily, many people understood what British Wildlife was trying to achieve, and we soon had articles from some of the seminal voices of the time. Derek Ratcliffe first wrote for the magazine in its second issue. This was a stinging rebuke to the government concerning the breaking-up of the NCC (BW 1: 89–91) – I can still remember the fire in his eyes as he described what was going on. Later he authored two masterful articles on ‘Upland birds and their conservation’ (BW 2: 1–12) and on the ‘Mountain flora of Britain and Ireland’ (BW 3: 10–21). Chris Mead, of the British Trust for Ornithology, was a great voice for birds and conservation, and enthusiastically backed British Wildlife from the start, contributing the birds report until his untimely death in 2003. Another important commentator on conservation was Colin Tubbs of NCC/English Nature. He took a much wider view on matters than most, and several of his contributions in the 1990s introduced a more international flavour to the magazine.

Often, important topics were being raised in British Wildlife years, if not decades, before they became part of the general discourse of the national media. A good example of this is a superb article by Alan Rayner published in 1993 on the ‘Fundamental importance of fungi in woodlands’ (BW 4: 205–215), in which Alan explains the intricate nature of the relationship between such things as mycorrhizal fungi and woodland health. We published an article on ‘Climate change and British Wildlife’ back in 1994 (BW 5: 169–179). An early article that caused much controversy was one on woodland management, ‘Biodiversity conservation in Britain: science replacing tradition’, by Clive Hambler and Martin Speight (BW 6: 137–147). British Wildlife has always been open to occasionally ‘stirring the pot’, but this piece boiled over into a debate that reached the national newspapers. It precipitated several excellent articles in response, including from Martin Warren, who had regularly written on the conservation of butterflies from the first volume. Also gathering impetus in the early 1990s was the idea of creating ‘wilderness areas’, as opposed to using more traditional farming practices. Contributions from Tony Whitbread and Bill Jenman (‘A natural method of conserving biodiversity in Britain’, BW 7: 84–93) and a reply from Colin Tubbs (BW 7: 290–296) are an example of an early skirmish from almost a quarter of a century ago.

It was pleasing to introduce Robert Burton, with his regular column, ‘Through a naturalist’s eyes’, in 1995. Each of his columns is a wonderfully crafted piece of natural history observation. Bill Sutherland, now Miriam Rothschild Professor of Conservation Biology at the University of Cambridge, first started the ‘Habitat management news’ section back in 1992 and his renowned evidence-based approach to wildlife management was clear even then. Some of the identification articles have been illustrated by Richard Lewington’s wonderfully accurate artworks and, indeed, were occasionally a testbed for some of the field guides that we were later to publish.

—————————-

Discover British Wildlife here.