Daringly innovative when it opened in 1848, the Palm House in Kew Gardens remains one of the most beautiful glass buildings in the world today

Daringly innovative when it opened in 1848, the Palm House in Kew Gardens remains one of the most beautiful glass buildings in the world today

In Palace of Palms, Kate Teltscher tells the extraordinary story of its creation and of the Victorians’ obsession with the palms that filled it: a story of breathtaking ambition and scientific discovery and, crucially, of the remarkable men whose vision it was.

Cultural historian and author, Kate Teltscher kindly took some time to answer our questions about her new book.

Can you tell us something about your background and what motivated you to write Palace of Palms?

Can you tell us something about your background and what motivated you to write Palace of Palms?

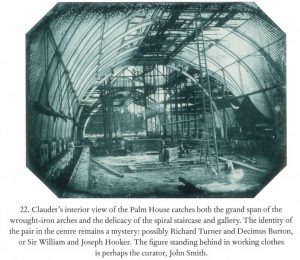

I’ve visited Kew since my childhood and have always loved the Palm House. It’s such a magnificent building, and just astounds you, the moment that you enter the Gardens. It’s so sleek and elegant, and modern-looking. As soon as you push open the door, the heat hits you, and you’re inside this tropical world. The architecture and plants combine to form this astonishing spectacle. The whole Gardens are landscaped around the Palm House, and the three long vistas at the back mean that you’re always catching sight of the Palm House as you walk the grounds. I wanted to find out why the Palm House was at the centre of Kew. Why was it the first building to be commissioned when Kew became a public institution? As a cultural historian, I was interested in the story that the Palm House could tell about Britain and botany, about palms and empire. And then in the course of my research I became fascinated by the characters that I discovered: the ambitious first Director, the self-taught engineer, and the surly yet devoted Curator.

The historical period in your book has been described as ‘The Golden Age of Botany.’ Do you think this description is justified?

The period certainly saw the birth of modern botany and many plant collecting expeditions, but the idea of a ‘golden age’ seems outdated now. The phrase tends to obscure or gild botany’s connection with commerce and empire. From its very foundation as a public garden, Kew had close links with colonial gardens across the empire. John Lindley, the botanist who wrote a government report on Kew, proposed that the colonies would offer up their natural resources to Britain to aid ‘the mother country in every thing that is useful in the vegetable kingdom’. Kew was seen as the co-ordinating hub of a network of colonial gardens in India, Australia, the Indian Ocean and the West Indies, that would exchange information and plants across the globe. Transplanting medicinal plants, economic and food crops across continents, Kew engineered environmental and social change worldwide.

Why were palms so important to the Victorians?

Why were palms so important to the Victorians?

The Victorians inherited the great Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus’ notion that palms were the ‘princes of the vegetable kingdom’. They were regarded as the noblest of all plants, far surpassing all European vegetation. For the public educator, Charles Knight, they combined ‘the highest imaginable beauty with the utmost imaginable utility’. They provided every necessity of life: food, drink, oil, clothes, shelter, weapons, tools and books. They were so bountiful that Linnaeus imagined that early humanity had subsisted entirely on palms. As Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal put it: the question is not ‘What do they afford us? But what is there that they do not?’

Your book is full of intrigue, exploration and innovation. During your research was there one fact or event that stood out as been particularly remarkable?

I was particularly struck by the change in status of palm oil between the 1840s and today. Industrial chemists had recently discovered the properties of palm oil that would, in our own time, make it one of the most ubiquitous of vegetable oils. In the nineteenth century, palm oil was used as axle grease on the railways and, combined with coconut oil, as a constituent of soap and candles. The oil palm grew in the areas of West Africa previously dominated by the slave trade. The trade in palm oil, it was argued, was the most effective means to combat human trafficking. In contrast to current fears that palm oil production is a major cause of deforestation and involves child and forced labour, the Victorians viewed palm oil as an ethical product, with unlimited manufacturing possibilities.

How do you envisage the future of the Palm House, the finest surviving Victorian glass and iron building in the world?

How do you envisage the future of the Palm House, the finest surviving Victorian glass and iron building in the world?

I understand from Aimée Felton, the architect who compiled a report on the Palm House, that despite the constant humidity of the interior, the actual structure is in reasonably good shape. These days, I guess, the Palm House does not look so big. Some of the tallest palms can never reach maturity because the Palm House roof is not high enough; they have to be cut down so that they don’t break through the glass. Obviously modern plant houses, like the Eden Project biospheres or the Norman Foster-designed Great Glass House at the National Botanic Garden of Wales may be larger or wider. But what I find interesting is that these plant houses, like the Palm House, are daring, experimental structures. The Palm House really functioned as the model for glasshouses across the globe throughout the nineteenth century: in Copenhagen, Adelaide, Brussels, San Francisco, Vienna and New York. From a contemporary point of view, the Palm House is often seen as a forerunner of twentieth-century modernism. It offers a perfect union of form and function, with its clean lines and organic shape. In recent years, the Palm House has provided the inspiration for one of London’s current icons: the London Eye. I expect that it will go on inspiring architects and engineers for years to come!

Are you working on any new projects you can tell us about?

I’m hoping to work more with Kew, in particular a project to digitise an early record book that documents all the plants that were received and sent out from Kew at the end of the eighteenth century. Since Kew was the first point of entry for many plants into Britain, and also sent plants to colonial botanic gardens all over the world, this record book is central to our understanding of the circulation of plant species, both nationally and globally. Kew really is a place of infinite riches, for the visitor and historian alike!

Palace of Palms: Tropical Dreams and the Making of Kew

Palace of Palms: Tropical Dreams and the Making of Kew

By: Kate Teltscher

Hardback | July 2020| £19.99 £25.00

The extraordinary history of the magnificent Victorian Palace of Palms in the Royal Botanic Garden, Kew.

Further Reading

Discover more about natural history explorers and their discoveries in our selection of books.

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.